Dear respected administration members,

I am writing today to express my deepest concern over your recent termination of head XC and Track coach, Steve Boyd. I am a resident of Kingston, the daughter of two Queen’s alumni, and a member of Steve’s elite distance running club, Physi-Kult.

On February 8, 2020 I was among the many Canadians to recoil in horror upon reading the Globe and Mail cover story about Megan Brown, the abuse she suffered at the hands of Dave Scott-Thomas and the subsequent cover up conducted at the institutional level to deny and hide her story. I felt a fierce rage burn inside of me that I’m certain every person who read the details of her account did as well. And yet, the pain that her story inflicted also felt incredibly personal: like Megan, I began running as a young girl to cope with the sudden death of my mother; like Megan, I was sexually assaulted and have spent a significant portion of my life processing and recovering from the trauma. Unlike Megan, however, I didn’t report my assault to the administrations that would have been responsible for pursuing justice and so avoided the bureaucratic silencing that she experienced. And unlike Megan, when I began to acknowledge my experience and seek help, I found in my running community above all, the support that I needed. The role of my coach, Steve Boyd, in helping me to use running as a way to confront and overcome my trauma cannot be understated.

On June 9, 2003 my mum, Leslie Langley, died suddenly at the age of 42. I was the youngest of her six children at the age of only 8. Too young to process such a significant loss at the time, I didn’t begin to feel the weight of her death until I entered my adolescence. To cope with the sudden influx of confusing and powerful emotions, I began running. While I found consolation at first by running alone, it was when I was invited to join Steve’s local running club, Physi-Kult, that I developed a much deeper connection to the sport and to my healing process. Throughout high school, I would meet twice a week with a group of 15-20 other runners, ranging in age and ability. Steve’s group connected me to other high school students from across the city, as well as to masters runners who were pursuing the sport competitively in their adulthood. Steve fostered an incredibly supportive and fun environment by encouraging, guiding and celebrating the progress of each individual athlete. He treated us all as equals and that gave me a sense of worth and purpose at a critical time in my life. The loneliness I felt as a result of my mum’s passing was softened by the camaraderie and kindness of my teammates and coach.

Under Steve’s coaching, I succeeded enough as a high-school runner to obtain an athletic scholarship to a division I NCAA institution in the United States. During my four years in the NCAA, I encountered a completely different side of the sport, one rampant with casual though nevertheless egregious sexism. I felt constantly demeaned by my coaches, who seemed to never see me as the capable, intelligent, and ambitious individual I knew myself to be, instead only ever as a girl. The women’s team was told on a regular basis that we were overly emotional, scared to compete; that we had an “attitude problem” and that’s why we didn’t race well. We were told that no matter what we did on the track, it wouldn’t affect the grand scheme of things because we were going to be “great mothers and wives someday.” When we did compete well, our accomplishments were trivialized. For example, when we were presented with hard-won conference championship rings one year, we were told to be proud “even though they [weren’t] the rings we came to school for.” I watched as my male teammates received remarkably different treatment and better coaching. I listened to our team “nutritionist” who encouraged the women’s team to watch calories, when in a separate meeting she spoke to the men’s team about the importance of refueling. I internalized the body-shaming comments my coach made about us behind our backs to members of the men’s team. I began to police myself and others about what we were consuming and in doing so, not only did I develop a ravage case of bulimia as a result, I also contributed in my way to maintaining an insidious culture of disordered eating and body image on my team. What we are learning through the powerful testimonies of female athletes across Canada and the U.S. is that this sort of environment is pervasive and occurs in women’s running programs everywhere.

During the summer of my sophomore year, I was one of the few students to stay on campus for the June/July semester. After attending a small party in a neighbouring campus apartment, I was raped in my bedroom by a fellow student-athlete. I spent the next year denying what happened to me, telling myself the same story: I was not raped. I must have said “yes” eventually. Even if I was raped, it was my fault for drinking too much, for inviting him to my place, for blacking out. It wasn’t until the fall of 2016 when I could no longer accept these things that I was telling myself. Inspired by a feminist theory course I was taking at the time, I decided to tell an acquaintance about what happened. The response I got? “How do I know you’re telling the truth?” I vowed then to not report my assault, and more generally not to speak about it again.

After a particularly bad race in California in the Spring of 2017, after which my coaches did not say a word to me, I quit my university’s track team. I hated running enough by then that I seriously considered quitting the sport for keeps. The only reason I didn’t was because I knew of the running culture and the people I would soon be returning to in Kingston. Sure enough, I was welcomed back by Steve, Physi-Kult and his Queen’s team. I instantly felt my love for the sport and its people return.

Eventually, though, my trauma caught up to me and I got incredibly ill. I experienced months of deep depression, the self-harm tendencies of which manifested in the relic of my time in the NCAA: bulimia. In August 2018, I started an out-patient treatment program at a local “Adults with Eating Disorders” clinic, as well as intensive psychotherapy. The effects of these treatments combined with the effects of trialling various medications to stabilize my mood, took a significant toll on my training. When I spoke to Steve about what I was going through, he encouraged me to put my health above my running. He made it clear to me that I had a place in his group and the broader running community even if I decided not to train or compete at a high level. He understood and supported me when I told him I needed to step away from the sport. He didn’t make me feel ashamed or embarrassed when I returned to competition and was racing at a level far below my previous standards. He simply adjusted the training plans and told me to take it day by day. He was patient and kind, as he always had been.

I look back at this period of time with some astonishment: at my worst, I was seriously suicidal. In the darkest moments I would think, “this pain will never end. Tonight is the night.” And yet, another thought would surface: “what about holding on for at least one more run?” I don’t add this for dramatic effect, but on several occasions, the promise of another run and sharing my love for the sport with my coach and team saved my life.

This brings me back to Megan Brown. What if she had had a coach like Steve who was as committed to her development as a person as he was to her development as an athlete? What if she had found in her running community the support and love that I have? What if we had believed her story and protected her? These and other “what if” questions are haunting, almost too tragic to consider. But at this point of reckoning in our sport, surely some tough questions need to be asked and answered.

The rise of the #MeToo movement in recent years has shed light on the dimensions of our society’s rape culture. Rape culture refers to the broader structures of inequality that allow for the normalization of gender-based (and often race and class-based as well) abuse and assault, which can encompass a range of attitudes and actions from cat-calling, addressing women as “girls,” to rape or even murder. One of #MeToo’s key insights is in its exposure of the machinery of “silencing”; the mechanisms in place at nearly every level, but most powerfully at the institutional level, to discourage women from sharing their stories, to discredit those who do share their stories, and to ultimately protect individual perpetrators of sexism, sexual harassment and violence. What the Globe and Mail article did so well to reveal was how Megan Brown’s story fits into this pattern of rape culture. Her story wasn’t just about the horrific actions of one man, isolated in his own perversion. Her story was also about the systems that cruelly toiled to cover for his crimes and abuses. The article thus implored us to see beyond Scott-Thomas to the wider dynamics of power at play. One takeaway, then, was that the power of institutions to silence stories of abuse is vast. This fact helps to explain the phenomenon of under-reporting of sexual assaults that exists today. Indeed, reading her story, I admittedly told myself “this is why I didn’t report my assault to authorities.”

It was exceptionally troubling, then, to hear of Steve’s termination from Queen’s over his speaking out against the abuse that occurred at Guelph. Queen’s was presented with an opportunity to stand behind Steve, who has always been outspoken in his commitments to challenging inequality and its various forms of damage. In firing him, Queen’s has instead proved itself to be an institution complicit in the perpetuation of the very conditions of rape culture: one that would prefer to protect its own reputation at the cost of shrouding conversations about stories like mine and Megan Brown’s in anonymity and silence.

I am compelled today, roughly four years after I vowed to forget about my assault, to speak up. In the tradition of “consciousness-raising” set out by radical feminist politics before me, I hope that adding my story to the body of #MeToo will help to shape the discussion of gender-based violence and accountability that happens from here. If sharing my story accomplishes anything, however, let it be to prove a point to Queen’s: your efforts to further silence the conversation have failed.

To close, I am calling for you to reconsider and rescind your termination of Steve. I hope that I have made clear that our sport is in desperate need of coaches like him. You are doing an unmistakable disservice to your student-athletes by robbing them of their compassionate and principled leader.

Thank you very much for your time,

Clara Langley

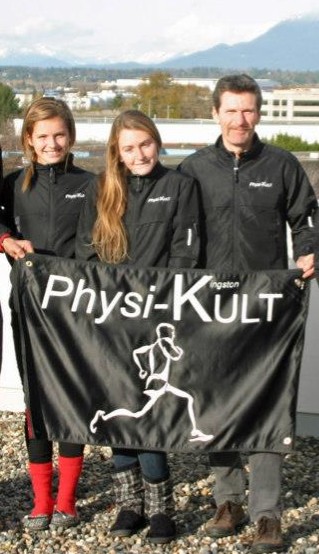

Pictures at the top, Langley, at left, with Cleo Boyd, Steve Boyd’s daughter, at their running club.

Our Magazine

Our Magazine

Very brave letter! Return Steve Boyd please!

Clara, you are truly an inspiration! Your Mom would be so proud of you! Thank you for having the courage to speak out! Wishing you the very best to come.

Hi Clara- Thanks for sharing the letter…I am an author working with a former Olympian who recently resigned at an American University when her complaints about inappropriate conduct by a male coach with female runners were ignored. Instead of acting to prptect the girls they labeled the woman a troubemaker and whistleblower and ordered her to shut up and coach. Thanks for your courage in sharing your story. I hope that it brings the results you are hoping for.

Best regards-Kyle Keiderling

http://www.keiderlingbooks.com

908-397-2518