Many would agree that climate change is the most important issue of our time.

Extreme weather patterns, rising sea levels, and unpredictable environmental, social, and economic impacts all factor in to this pending crisis. Thanks to films An Inconvenient Truth and National Geographic’s Before The Flood, as well as global movements like the climate strikes in more than 150 countries this September led by teenager Greta Thunberg, there has been a shift in the thought of climate change: act now.

As it stands, much of the publicized effects of climate change, like rising sea levels and the melting of Arctic ice, are relatively unseen by most. Out of sight, out of mind, right? Well, as we explore below, the trickle-down effects of climate change, including for runners who view the sport as near-sacred, are becoming increasingly apparent. And, as science suggests, we’re trending in the wrong direction.

State of the climate

Climate change refers to a long-term shift in weather conditions as measured by various factors including temperature, precipitation, winds and a few other metrics. However, naturally, the world’s climate is variable over time.

Ever since the Industrial Revolution in the 18th and 19th centuries, human activity, thanks to a fossil fuel-driven economy, has drastically increased carbon dioxide emissions in the atmosphere, which affects the Earth’s energy balance. Carbon dioxide is the main cause of human-induced climate change, according to Environment Canada. Industrialization, deforestation, and large scale agriculture also have an effect on the world’s climate.

The effects of widespread warming are evident in many parts of Canada and are projected to intensify in the future. In Canada, these effects include more extreme heat, less extreme cold, longer growing seasons, shorter snow and ice cover seasons, earlier spring peak streamflow, thinning glaciers, thawing permafrost, and rising sea level. Because some further warming is unavoidable, these trends will continue, according to Environment Canada’s 442-page Canada’s Changing Climate Report.

How running is impacted

When we as runners are inconvenienced, that’s just a small sample size of the trickle-down effects of climate change. And perhaps those micro-effects could have the largest impact on our behaviour.

In recent years, several Canadian races have been cancelled directly due to the weather. In 2019, for example, organizers halted the Calgary Police Half-Marathon, while the Cape Fiddlers Marathon was cancelled because of Hurricane Dorion. Other notable events to fall victim include the Whistler 400 and Fat Dog 120 in 2017 and 2018, respectively, though this list is far from exhaustive.

However, forest fires, hurricanes and other extreme weather are normal in nature. But, what’s worrying is the intensification, and frequency of such events.

“Extreme hot temperatures will become more frequent and more intense,” Canada’s Changing Climate Report continues. “This will increase the severity of heat waves, and contribute to increased drought and wildfire risks. While inland flooding results from multiple factors, more intense rainfalls will increase urban flood risks.”

This is not to mention the impact that climate change would have on coastal cities.

Since 1993, the average rate of sea level rise is 3.2 mm per year, according to data from the World Meteorological Organization. What’s more alarming is that between May 2014 and 2019, the rise has increased to 5 mm per year. According to the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group, 570 low-lying coastal cities face drastic challenges within the next 50 years based on current projections. Two of those cities are home to marathons that Canadians love to travel to every year: New York City and Miami. When Hurricane Sandy hit coastal United States in 2012, race organizers — granted at the last-minute — cancelled the (then-) I.N.G. New York City Marathon because of floods and damage to the city’s infrastructure.

For coastal runners in Canada, the news isn’t good either. According to Environment Canada’s Changing Climate Report, “local sea level is projected to rise, and increase flooding, along most of the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of Canada.”

What’s clear is that running is vulnerable to external variables including extreme weather. But because races are one-offs each year, the likelihood of cancellation is quite low, so the impact may not be felt. What does, and will continue to, affect runners is the temperature.

In July, RunRepeat posted a study that analyzed a staggering amount of data — 19.6 million marathon results from over 30,000 marathons — and shared their results online. Titled, How Much is Climate Change Slowing Down Runners, the authors found that the average runner slows by 1:25 for his/her marathon finish time for each additional degree of Fahrenheit. (1 F = 0.56 C, roughly.)

A similar study, entitled, Effects of Warming Temperatures on Winning Times in the Boston Marathon, published in 2012, found that “a 1.6 C warming in annual temperatures in Boston between 1933 and 2004 did not consistently slow winning times because of high variability in temperatures on race day.” However, winning time was studied in that case, not the field’s average.

We spoke with Paul Ronto, RunRepeat’s Director of Content, who co-authored the research with Vania Andreeva Nikolova, who has a Ph.D. in Mathematical Analysis.

“Climate change is also causing drastic swings in temperatures causing issues like extremely high temperatures on race days like Chicago saw in 2007,” he says. And who can forget Boston’s history? Since 2007, the race has experienced crazy winds, sweltering heat, and near-freezing temperatures, all within just over a decade.

Because a runner’s time is so dependent on a variety of external (let alone internal) factors, it’s tough to pinpoint the exact effect of heat. We asked Ronto how they concluded the link between temperature rise and the slowing of finish times.

“What we did in this study was to look specifically at average finish time and temperatures to see if there was any direct correlation and we found that temperatures on race day are responsible for over 30% of finish time variances, which puts temperatures as one of the largest factors in runner’s finish times,” Ronto says.

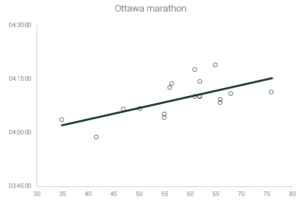

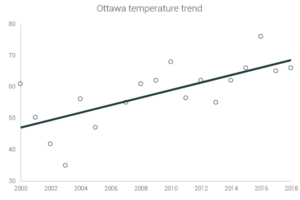

For example, Ronto sent over data specific to the Scotiabank Ottawa Marathon that shows the trend remains true for the nation’s capital. “Again a strong correlation to finish times and temperatures,” he says.

“I think it’s a great anecdote for how pervasive this issue [climate change] really is,” he says. “What’s surprising is that no one talks about the small changes we are seeing, they talk about rising sea levels and melting ice caps, but those are not accessible to the everyday person. What other daily tasks like running are affected by climate change? My hope is that these small changes that affect everyone are the catalyst of change.”

Perhaps it’s when these small changes, inconveniences if you will, begin to disrupt our daily lives in an impactful way that we will see change on the most basic level.

What’s being done

Climate change has changed the way organizers plan races.

The Scotiabank Toronto Waterfront Marathon, Canada’s top marathon which hosts more than 25,000 runners each year, has a number of initiatives in place to accommodate the changing climate, and to reduce its footprint.

To get an idea of how Canada Running Series, the organizers of the race, handles unpredictable weather, we chatted with event director Charlotte Brookes. “Weather and climate change has definitely shifted the way we plan for events and what we need to consider due to how unpredictable the weather has proven to be regardless of season.”

A combination of working with local organizations and the city to build out a contingency plan, adopting a world-class alert system, and communication with participants ensures that organizers are ready for a variety of conditions on race day. “We have lightning detectors, wet bulb globe thermometers, policies and plans around wind levels as well as lightning/thunder proximity thresholds and for the first time this year we have started using Weather Ops through Odyssey Medical with an on-call meteorologist.”

In terms of what’s being done, the Scotiabank Toronto Waterfront Marathon is one of the leaders in the sport.

Speaking to Parvati Magazine, race director Alan Brookes says, “we were the first-ever event in Toronto to receive Gold level certification by the Council for Responsible Sport. Our races are bottle-free, and registration is paperless. Our cups are composted. All leftover food is donated to Second Harvest. We’re always looking to improve our green plans and are working to implement new measures and improve existing efforts at our events.”

Meanwhile, the New York Road Runners, the organizers of the New York City Marathon, recently signed on to the UNFCCC’s Sports for Climate Action Framework in striving towards sustainability.

Off the roads, select Canadian trail races are cup-less at water stations, encouraging participants to bring their own reusable bottles to reduce single-use plastics.

On the brand side, New Balance recently announced two major climate commitments focused on cutting emissions and relying on sustainable energy sources. Here in Canada, MEC is shutting all of its stores so employees have time off to attend the climate strikes.

“We are members of this Co-op because we share a love of the outdoors,” says MEC CEO Phil Arrata. “It’s time to act so we can protect it for generations to come.”

How bad will it get before we’re able to implement major change? Time will tell.

Our Magazine

Our Magazine